Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology

How Gunpei Yokoi reinvented Nintendo and created the Game Boy.

I.

In 1965, a young Japanese man named Gunpei Yokoi graduated from a university in Kyoto. Many of his classmates had landed lucrative jobs at reputable firms and flocked to Tokyo, but Yokoi had trouble securing interviews. When his classmates asked about his career plans, he answered, "I never had a specific dream for my work." Yokoi wanted to stay in his hometown but had no interest in his family’s pharmaceutical business. Desperate, he applied for a maintenance job at a local company that made a Japanese playing card game called hanafuda—literally “flower cards.”

The company's name was Nintendo.

Since opening its doors as a small wooden shop in 1889, Nintendo had grown into a successful hanafuda business, but the company was in trouble when Yokoi joined. As Japan's economy boomed leading up to the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, the public shifted to flashier entertainment options like bowling and pachinko gambling slot machines. Nintendo’s sales plummeted as traditional card games fell out of favor. The company president took on debt and ventured into taxi services, rent-by-the-hour "love hotels," and instant rice with cartoon packaging, but all the efforts failed.

As the company's only maintenance staff, Yokoi oiled the dusty printing machines and fixed the conveyor belts when they broke. He didn’t mind the mundane responsibilities. “I thought if I could work in peace until retirement, anything was fine,” he recalled. Business was slow, so Yokoi had plenty of idle time.

Outside of work, Yokoi had diverse interests in music, ballroom dancing, and fixing cars. His favorite hobby was monotsukuri—literally "things making" in Japanese. In middle school, he enjoyed building elaborate miniature model railways. When he started driving, Yokoi taped a recorder to his car stereo to record his favorite radio programs.

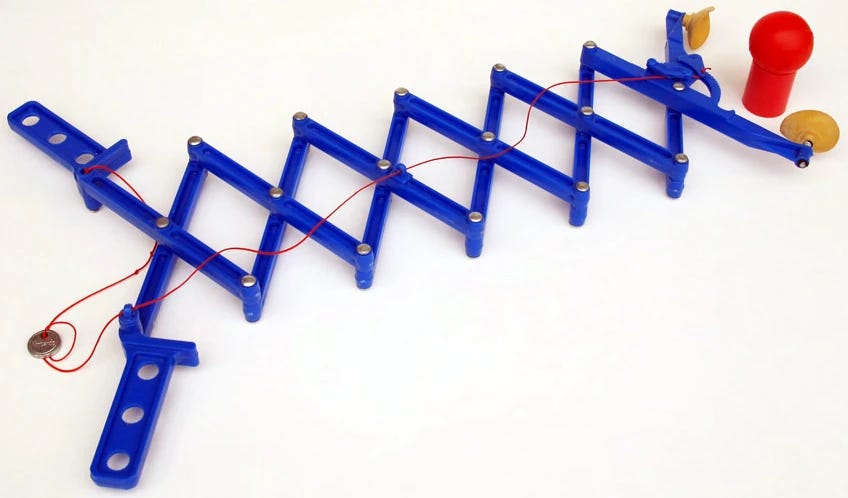

With the free time at work, Yokoi tinkered with spare parts to amuse himself. One of his cheeky inventions was a pair of tongs made of crisscrossed pieces of wood with an extendable arm and a gripping tool at the end. Yokoi took pride in grabbing small objects from a distance with little effort.

Nintendo's president, who had hired Yokoi, saw him goofing off and called him into the office. Yokoi thought he was in trouble, but instead, the executive asked him to turn his device into a game and make it a product.

“Make it a game?” he replied. “All it did was accordion in and out!”

Yokoi racked his brain over the request. The best thing he came up with was to add a set of colored balls and cups. He thought the arm would at least have something to grab, and kids could have a stacking competition. This package didn’t seem promising, but the company president approved it.

By Christmas of 1966, Nintendo's first toy, Ultra Hand, hit the market at about 800 yen, or roughly $6.

It sold over a million units.

II.

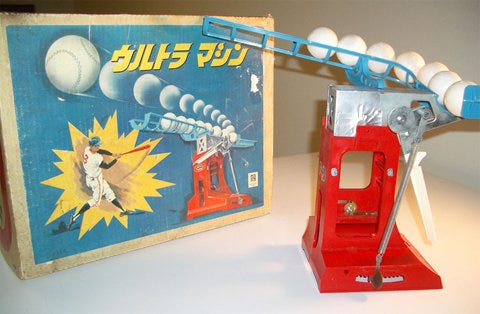

After Ultra Hand's success, Nintendo's president pulled Yokoi off the assembly line and asked him to focus on product research and development. Yokoi’s next successful project was the Ultra Machine, a softball pitching device with a small bat included.

Another hit was the Love Tester, a device that measured two people's "love" on a scale of 1 to 100. The toy measured electric conductance when two people touched the round metal handles with one hand while joining their free hands. Love Tester was immensely popular among Japanese teenagers, as it gave them an excuse to hold hands in a country where physical contact is considered taboo.

"The Love Tester came from me wondering if I could somehow use this to get girls to hold my hand," Yokoi recalled. "I wound up holding hands with quite a few girls thanks to it." Conveniently, sweaty palms increased conductivity and led to a higher reading. "I loved explaining that the meter gave better results when people kissed the girl."

Yokoi had flops, too. One setback was a tabletop unit for a player to use a steering wheel to control a plastic car along a racetrack powered by an electric motor. However, the design was fragile, expensive, and prone to defects. Despite having a degree in electronics, Yokoi's engineering skills and experience were limited. The failure taught him the value of simple designs with reliable components.

One day, while on board a bullet train back to Kyoto, Yokoi saw a bored businessman punching buttons on a calculator to pass the time. An idea arose: would commuters want to play games on a small screen?

As he mulled over the idea, Yokoi received a call from the head of human resources. The company president had a meeting downtown, but his chauffeur was sick. Yokoi was the only person in the company who could drive an American car with a steering wheel on the left.

The request annoyed Yokoi. “I took pride in being a department head,” he recalled. “I wasn’t anyone’s driver!” But refusing the boss was not an option.

While on the car ride, Yokoi realized it was an opportunity to share his latest idea without calling for a formal meeting.

“If we can make a game machine as small and thin as a calculator,” Yokoi told the president. “Salarymen can play games without getting busted!”

The president nodded but expressed little reaction.

A week later, a few executives visited Yokoi by surprise. It turned out the president had shared Yokoi's idea with the LCD calculator manufacturer Sharp. “You wanted to make a calculator-sized machine,” the president said. “Sharp’s good at that, so I called them over.”

As liquid-crystal display technology matured in the 1970s, the calculator market quickly saturated, so Sharp was eager to find new ways to sell its LCDs. While initially skeptical, Sharp sensed the potential of Yokoi’s idea and agreed to partner with Nintendo.

Over the next two years, Yokoi pushed the team to shrink the LCD screen size so the device could fit in anyone's palm. He added a tiny digital clock in the corner and branded the console Game & Watch as a final touch. At first, the device only had two buttons for controlling left and right. In the subsequent 1982 version, Yokoi added a distinctive plus-shaped button known as the directional pad, or "D-pad," so players could maneuver a game character in all four directions.

Nintendo sold 40 million units of Game & Watch within a decade, including the classic games Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros, and Tetris. Bolstered by Game & Watch's popularity, Nintendo used similar technologies and built a follow-on product called the Nintendo Entertainment System. The NES would connect to a TV without its own display.

The combined success of Game & Watch and NES brought Nintendo's products to over 100 million homes and created fans around the world.

But this still paled compared to Yokoi's most iconic product to come: the Game Boy.

III.

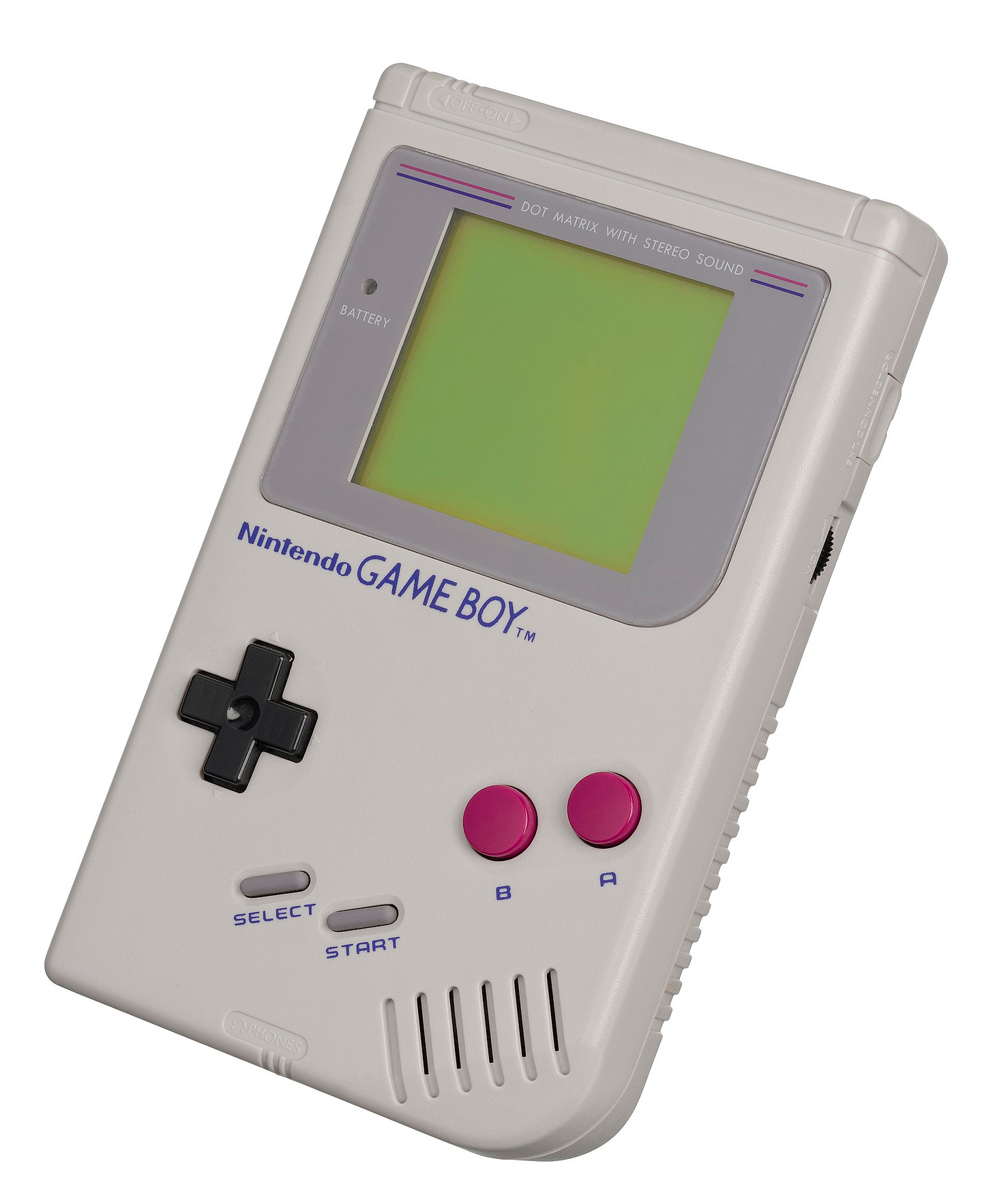

Even by the standard of the early '90s, the Game Boy's technology was inferior. Competitors like Sega and Atari released handheld game systems with fancy backlit color screens and state-of-the-art processors. The Game Boy featured an outdated processor on a small monochrome display with four shades of gray on a green background, a visual experience arguably worse than Nintendo's own NES.

The deliberate choice to compromise on technology was hotly debated within Nintendo. Many argued that the Game Boy couldn't compete with hardware and graphics quality from the previous generation, but Yokoi disagreed. From his perspective, using cheaper components would allow Nintendo to price the Game Boy at half the competition's price, making it affordable for an average family.

A simple design with proven hardware had another advantage: reliability. Since Yokoi's team had a decade of experience with monochrome LCDs, 8-bit processors, and the D-pad, they knew how to minimize defects and keep quality high. The Game Boy's build was so sturdy that even if someone put the device through a washing machine (as I did once as a child), it would survive after drying out for a day or two. Less complexity also meant less power consumed: Four AA batteries allowed for days, sometimes weeks, of playtime.

In contrast, Sega and Atari's devices had many problems with their complex hardware. Gamers were disappointed when fresh batteries yielded only a few hours of playtime.

In addition to attracting customers with low cost, durability, and long battery life, the Game Boy’s familiar technology also made it easy for game developers to iterate on existing games and build new ones. As a result, Game Boy rapidly grew an extensive game library, including variations of the most beloved games like Pokemon, Super Mario Land, and The Final Fantasy. A virtuous cycle formed: more games attracted more device sales, encouraging developers to produce more games. Over its life span, the Game Boy had 1,000 released game titles, compared to 300 on Sega and 70 on Atari.

The technologically least advanced device became the best-selling game console ever before 2000: the Game Boy sold over 118 million units worldwide.

IV.

While developing the Game Boy, Yokoi advocated a design philosophy: lateral thinking with withered technology. "Creativity isn't about chasing the newest tech trend," he said, "It's about finding ingenious ways to breathe new life into existing technology. That's the essence of lateral thinking with withered technology."

The concept of lateral thinking was first coined by Maltese physician Edward De Bono in the 1960s. De Bono observed that humans use two modes of thinking: vertical and lateral. Vertical thinking follows a linear process to solve problems based on rules, reason, and logic. It seeks to converge on a correct answer and exclude other possibilities, like concluding that one plus two must be three. Vertical thinking is tremendously useful: it helps us do arithmetic, study science, and write grammatical sentences. We rely on it to solve analytical problems, plan efficient trips, and make reasonable decisions.

Vertical thinking, however, has limitations when objectives and structures are unclear. Challenges in a chaotic and uncertain world are often ambiguous without a known answer. Unlocking a path forward usually requires reframing the problem and breaking free of traditional patterns. In such a situation, lateral thinking can be invaluable as an additional tool.

The word lateral comes from the Latin word latus, meaning side. Instead of looking for a step-by-step solution, a lateral thinker looks sideways, zigzags between subjects, and mixes concepts from various domains to arrive at fresh ideas. Lateral thinking avoids applying a fixed label on an object or a premature judgment to an idea. "If you think vertically, a calculator will end up a calculator," Yokoi said. Instead, a lateral thinker generates many ideas through play and experimentation. A calculator, for example, can be a vehicle to deliver fun when applied in a new context, as Yokoi’s story illustrated.

The psychologist William James explored a similar idea nearly a century before De Bono, even though he didn't call it lateral thinking. In his Atlantic article published in 1880, James argued that great ideas often come from the "most unheard of combination of elements" through "abrupt cross-cuts and transitions from one idea to another" rather than following “a beaten track.” Yokoi's Love Tester fits neatly in James's description: Electrical conductivity and a conversation starter with a romantic interest was a highly unusual, if not absurd, combination. Yet, the invention struck a chord: Love Testers are still in arcades today.

Yokoi's approach to lateral thinking was, in many ways, born out of necessity. When Nintendo first ventured beyond playing cards, established Japanese companies like Bandai and Tomy had already dominated the toy market. Yokoi couldn’t compete on money, scale, or market influence against the giants. His limited engineering knowledge and manufacturing experience also constrained him to make anything complex. "I don't have any particular specialist skills," he said. "I have a sort of vague knowledge of everything." Counterintuitively, these financial and technical limitations fostered lateral thinking. He built scrappy things with whatever materials were within reach. This practice encouraged him to improvise, recycle old ideas, and discover creative combinations most people had overlooked.

The initial success of Ultra Hand might have been fortunate—no one predicted Yokoi’s makeshift extendable arm to be a massive hit—but it demonstrated the benefits of his approach. First, it’s okay to explore without knowing the precise destination. An open, unencumbered mind is valuable. Second, surprising results can emerge when old components are connected in new ways, even if the individual components seem ordinary on their own. Third, an inventor is often a poor judge of his own invention. Instead of evaluating an idea in one’s mind, it is often better to prototype it in real life and see what happens.

V.

The second part of Yokoi's philosophy—withered technology—emphasizes using mature technological components that are abundant and affordable. While idealistic, Yokoi was pragmatic in maximizing success and reducing risks. Old components are reliable and easy to use because they are well-understood. Low cost also makes it cheaper to experiment, test, and build a product.

Yokoi estimated that if he had released Game & Watch five years earlier, it would have cost 100,000 yen apiece, making it an unviable idea. As LCD became abundant, "it became cheaper and cheaper due to the mass production effect, and [Game & Watch] became 3,800 yen," he said.

Beyond cost and reliability, using seasoned technology was a guardrail to force discipline. As an engineer, Yokoi knew the risk of open-ended development with unlimited resources. "Engineers want to show off their skills, so they dream of using cutting-edge technology," Yokoi said. "They will make products that can't be sold." His self-imposed constraint of using only easily accessible components sharpens his focus. It avoids the temptation to blindly pursue shiny technologies that appear promising on the surface but are often fraught with unforeseen problems.

While his competitors engaged in an arms race for computer power, Yokoi played a different game. He focused on what mattered most to his audience: a fun, novel, and engaging experience at an affordable price. Once he developed a rough sense of what software could deliver that experience, he devised minimal hardware to fulfill it.

"That approach resulted in a very efficient product. Hardware design isn't about making the most powerful thing you can." Yokoi said. "The Game Boy was never about pushing the boundaries of technology, but about delivering an experience that was accessible and enjoyable for everyone."

Yokoi died in 1997 in an unfortunate car accident, but his lateral thinking with withered technology philosophy lived on. Every Nintendo product is based on proven components from the past while making a few tweaks. The cross-shaped D-pad in Game & Watch has been used in virtually all of Nintendo's game consoles since the 1980s. Nintendo released the Wii console in 2006 based on the design of the NES but improved graphics and added a wireless motion sensor controller. Nintendo Wii, released in 2017, was essentially a remix of the Wii and the Game Boy: it connects to a TV but also has a built-in screen.

After Yokoi's death, Nintendo remains one of the world’s most innovative gaming companies in the world, even though its game consoles have never as powerful as Sony's PlayStation and Microsoft's Xbox.

VI.

Since the day he accidentally invented the Ultra Hand, Yokoi built a prolific career over his three decades at Nintendo, with dozens of toys and games under his name. Many were average, but a few products—notably Game & Watch and the Game Boy—defined his legacy as a video game designer. From early on, Yokoi understood that lateral thinking is a meandering process, a continuous journey of discovery. A mediocre idea is a building block for a better idea. Each success and failure becomes material that can be mixed and repurposed in an unforeseen situation with the potential for a surprising outcome. Yokoi’s preference for withered technology suggests newer and faster technology is not necessarily better. Old stuff has value, too.

Throughout his personal and professional life, Yokoi wrestled with various constraints—money, skills, knowledge, opportunities, and experience. Someone once asked Yokoi how he came up with innovative ideas under limiting circumstances. One question seems to have helped him the most.

“What can you do if you think about it laterally?”